The U.S. Fire Map Is Changing — And These Researchers Want to Get Ahead of It

There were 77,850 wildfires in the United States in 2025, and nearly half of those — 49% — ignited east of the Mississippi River, according to statistics released last week by the National Interagency Fire Center. That might come as a surprise to some in the West, who tend to believe they hold the monopoly on conflagrations (along with earthquakes, tsunamis, and megalomaniac tech billionaires).

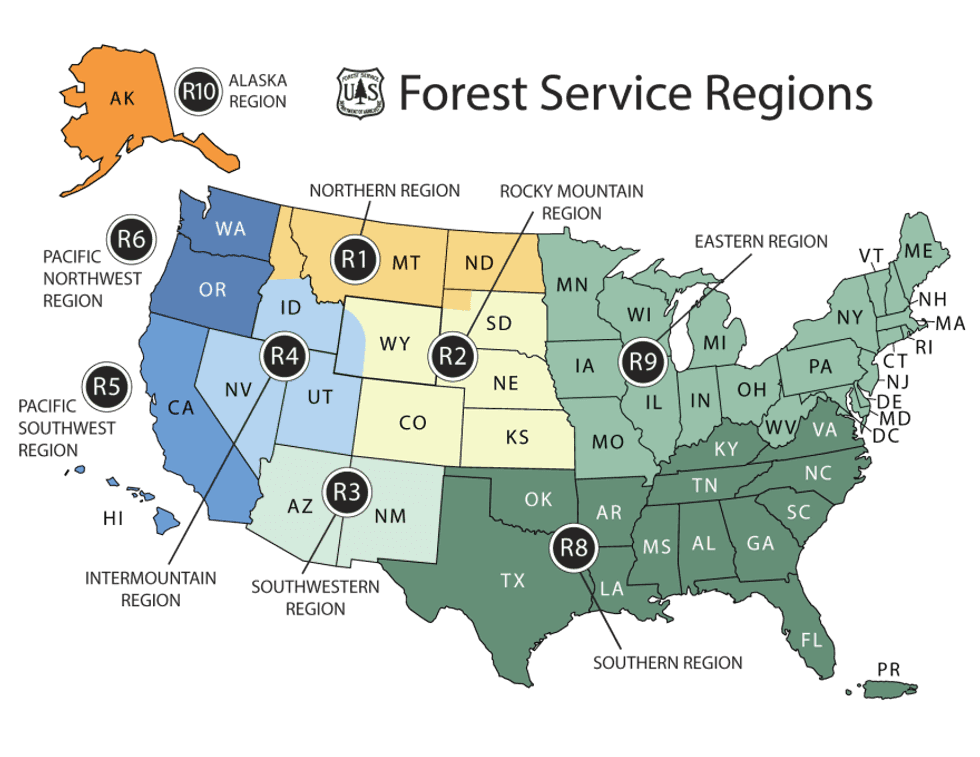

But if you lump the Central Plains and Midwest states of Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas along with everything to their east — the swath of the nation collectively designated as the Eastern and Southern Regions by the U.S. Forest Service — the wildfires in the area made up more than two-thirds of total ignitions last year.

Like fires in the West, wildfires in the eastern and southeastern U.S. are increasing. Over the past 40 years, the region has seen a 10-fold jump in the frequency of large burns. (Many risk factors contribute to wildfires, including but not limited to climate change.)

What’s exciting to wildfire researchers and managers, though, is the idea that they could catch changes to the Eastern fire regime early, before the situation spirals into a feedback loop or results in a major tragedy. “We have the opportunity to get ahead of the wildfire problem in the East and to learn some of the lessons that we see in the West,” Donovan said.

Now that effort has an organizing body: the Eastern Fire Network. Headed by Erica Smithwick, a professor in Penn State’s geography department, the research group formed late last year with the help of a $1.7 million, three-year grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, a partner with the U.S. National Science Foundation, with the goal of creating an informed research agenda for studying fire in the East. “It was a very easy thing to have people buy into because the research questions are still wide open here,” Smithwick told me.

The Lonesome, Crowded East

Though the Eastern U.S. is finally exiting a three-week block of sub-freezing temperatures, the hot, dry days of summer are still far from most people’s minds. But the wildland-urban interface — that is, the high-fire-risk communities that abut tracts of undeveloped land — is more extensive in the East than in the West, with up to 72% of the land in some states qualifying as WUI. The region is also much more densely populated, meaning practically every wildfire that ignites has the potential to threaten human property and life.

It’s this density combined with the prevalent WUI that most significantly distinguishes Eastern fires from those in the comparatively rural West. One fire manager warned Smithwick that a worst-case-scenario wildfire could run across the entirety of New Jersey, the most populous state in the nation, in just 48 hours.

Generally speaking, though, wildfires in the East are much smaller than those in the West. The last megafire in the Forest Service’s Southern Region was as far west in its boundaries as you can get: the 2024 Smokehouse Creek fire in Texas and Oklahoma, which burned more than a million acres. The Eastern Region hasn’t had a megafire exceeding 100,000 acres in the modern era. For research purposes, a “large” wildfire in the East is typically defined as being 200 hectares or more in size, the equivalent of about 280 football fields; in the West, a “large” wildfire is twice that, 400 hectares or more.

But what the eastern half of the country lacks in total acres burned (for that statistic, Alaska edges out the Southern Region), it makes up for in the total number of reported ignitions. In 2025, for example, the state of Maine alone recorded 250 fires in August, more than doubling its previous record of just over 100 fires. “The East is highly fragmented,” Donovan, who is contributing to the Eastern Fire Network’s research, told me. “We have a lot of development here compared to the West, and so it’s much more challenging for fires to spread.”

Fires in the West tend to be long-duration events, burning for weeks or even months; fires in the East are often contained within 48 hours. In New Jersey, for example, “smaller, fragmented forests, which are broken up by numerous roads and the built environment, [allow] firefighters to move ahead of a wildfire to improve firebreaks and begin backfiring operations to help slow the forward progression,” a spokesperson for the New Jersey Forest Fire Service told me.

The parcelized nature of the eastern states is also reflected in who is responding to the fires. It is more common for state agencies and local departments — including many volunteer firefighting departments — to be the ones on the scene, Debbie Miley, the executive director of the National Wildfire Suppression Association, a trade group representing private wildland fire service contractors, told me by email. On the one hand, the local response makes sense; smaller fires require smaller teams to fight them. But the lack of a joint effort, even within a single state, means broader takeaways about mitigation and adaptation can be lost.

“Many eastern states have strong state forestry agencies and local departments that handle wildfire as part of an ‘all hazards’ portfolio,” Miley said. “In the West, there’s often a deeper bench of personnel and systems oriented around long-duration wildfire campaigns (though that varies by state).”

All of this feeds into why Smithwick believes the Eastern Fire Network is necessary: because of this “intermingling, at a very fine scale, of different jurisdictional boundaries,” conversations about fire management and the changing regimes in the region happen in parallel, rather than with meaningful coordination. Even within a single state, fire management might be divided between different agencies — such as the Game Commission and the Bureau of Forestry, which share fire management responsibilities in Pennsylvania. Fighting fires also often involves working with private landowners in the East; in the West, on the other hand, roughly two-thirds of wildfires burn on public land, which a single agency — e.g. the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, or Park Service — manages.

“Wildfire Risk Is Going to Be Different Than in the West”

But “wildfire risk is going to be different than in the West, and maybe more variable,” Smithwick told me. Identifying the appropriate research questions about that risk is one of the most important objectives of the Eastern Fire Network.

Bad wildfires are the result of fuel and weather conditions aligning. “We generally know what the fuels are [in the East] and how well they burn,” Smithwick said. But weather conditions and their variability are a greater question mark.

Nationally, fire and emergency managers rely on indices to predict fire-weather risk based on humidity, temperature, and wind. But while those indices are dialed in for the Western states, they’re less well understood in the East. “We hope to look at case studies of recent fires that have occurred in the 2024 and 2025 window to look at the antecedent conditions and to use those as case studies for better understanding the mechanisms that led to that wildfire,” Smithwick said.

Learning more about the climatological mechanisms driving dry spells in the region is another explicit goal. Knowing how dry spells evolve, and where, will help researchers and eventually policymakers to identify mitigation strategies for locations most at risk. Smithwick also expects to learn that some areas might not be at high risk: “We can tell you that this is not something your community needs to invest in right now,” she told me.

Different management practices, jurisdictions, terrains, and fuel types mean solutions in the East will look different from those in the West, too. As Donovan’s research has found, the unmanaged regrowth of forests in the northeast in particular after centuries of deforestation has led to an increase in trees and shrubs that are prone to wildfires. Due to the smaller forest tracts in the area, mechanical thinning is a more realistic solution in eastern forests than on large, sprawling, remote western lands.

Prescribed burns tend to be more common and more readily accepted practices in the East, too. Florida leads the nation in preventative fires, and the New Jersey Forest Fire Service aims to treat 25,000 acres of forest, grasslands, and marshlands with prescribed fire annually.

A Dry Thaw

The winter storms that swept across the Eastern and Southern regions of the United States last month have the potential to queue up a bad fire season once the land starts to thaw and eventually dry out. Though the picture in the Eastern Region is still coming into focus depending on what happens this spring, in the Southern region the storms have created “potential compaction of the abundant grasses across the Plains, in addition to ice damage in pine-dominant areas farther east,” the National Interagency Fire Center wrote in last Monday’s update to its nationwide fire outlook. (The nearly million-acre Pinelands of New Jersey are similarly a fire-adapted ecosystem and are “comparable in volatility to the chaparral shrublands found in California and southern Oregon,” the spokesperson told me.)

The compaction of grasses is significant because, although they will take longer to dry and become a fuel source, it will ultimately leave the Southern region covered with a dense, flammable fuel when summer is in full swing. Beyond the Plains, in the Southeast’s pine forests, the winter-damaged trees could cast “abundant” pine needles and “other fine debris” that could dry out and become flammable as soon as a few weeks from now. “Increased debris burning will also amplify ignitions and potential escapes, enhancing significant fire potential during warmer and drier weather that will return in short order,” NIFC goes on to warn.

Though the historically wet Northeast and humid Southeast seem like unlikely places to worry about large wildfires, as conditions change, nothing is certain. “If we learned anything from fire science over the past few decades, it’s that anywhere can burn under the right conditions,” Smithwick said. “We are burning in the tundra; we are burning in Canada; we are burning in all of these places that may not have been used to extreme wildfire situations.”

“These fires could have a large economic and social cost,” Smithwick added, “and we have not prepared for them.”