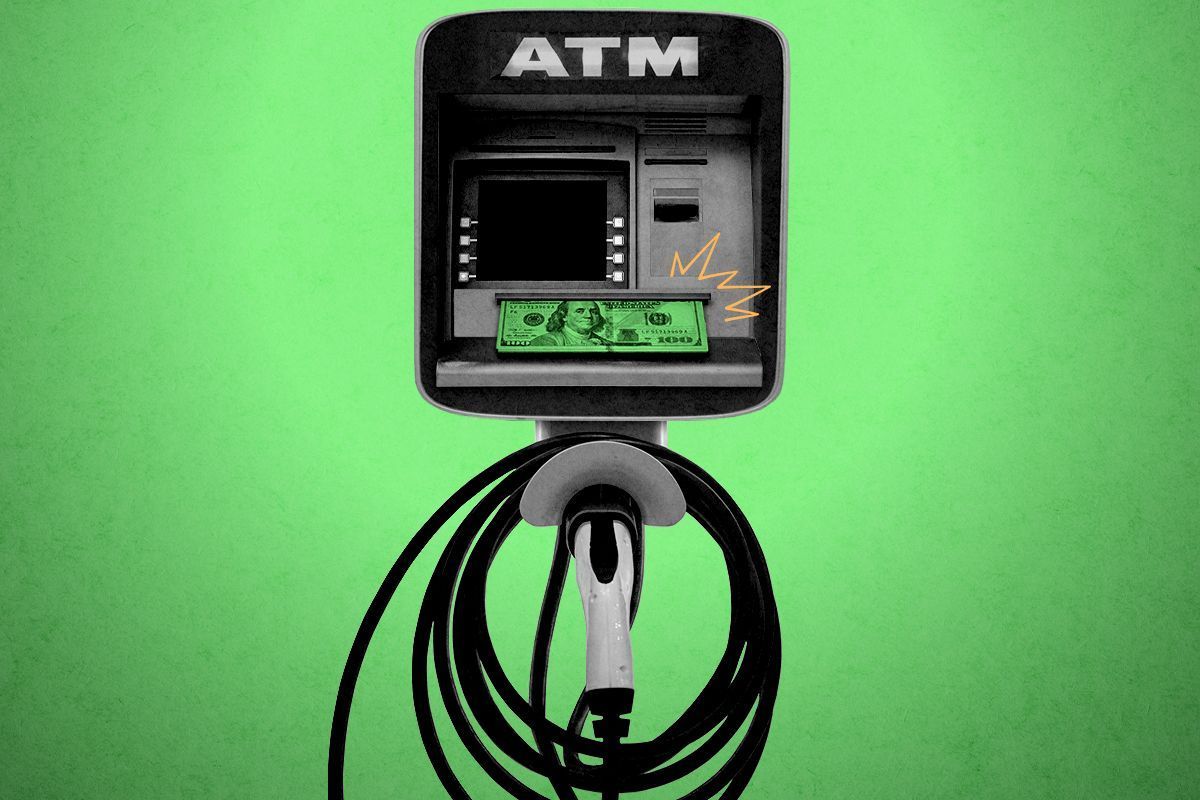

How EVs Could Help Lower Everyone’s Electricity Costs

One of the best arguments for electric vehicles is the promise of lower costs for the owner. Yes, EVs cost more upfront than comparable gas-powered cars, but electric cars are cheaper to fuel and should require less routine maintenance, too. (Say goodbye to the 3,000-mile oil change.)

What about the societal scale, though? As the number of EVs on the road continues to rise, more analysts are putting forth the argument that EV ownership could lead to lower energy bills for everyone, even the people who don’t buy them.

The idea may be counterintuitive, given the prevailing narrative about voracious appetite for electricity. EVs do require a lot of energy. Electricity demand for EVs in the U.S. jumped 50% from 2023 to 2024 alone as more Americans bought electric, and the research group Ev.energy says demand could triple by 2030. Studies suggest that replacing every internal combustion vehicle in the country with an EV would eat up as much as 29% of American electricity.

Meanwhile, the grid is struggling to keep up — it is, after all, much more difficult to add more megawatts to the capacity of our power system than it is to put a few more EVs on the road. The obvious inference would then seem to be that a battery-powered car fleet could cause an energy crunch and spike in prices.

A new report from Ev.energy, however, argues that if we got smarter about how and when we charge our cars, their presence could actually cut costs for the average American by 10%. The gains could be even better if EVs reach their true potential as a way to give the grid a unique kind of flexibility and resilience.

Compare an electric car to a data center, the other application painted as a ticking time bomb for electricity prices. Worries about the energy-gobbling habits of AI-powering servers are well-founded, given their 24/7 appetite. An EV, however, needs to charge only once in a while. In fact, most people don’t need to charge every day, given the range of modern EVs and the driving habits of the typical American.

As we've covered before, it’s when you charge that matters. Optimizing EV charging can be a helpful way to ease pressure on the power grid and align EV charging with the availability of clean energy.

Here in California, which has far and away the most EVs in America, TV commercials remind us to use less energy between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m., when the state is dealing with rising residential energy use just as solar power is tapering off for the day. It would cause a grid crisis if every EV owner charged as soon as they got home from work. Having EV owners charge their cars overnight, a period of low demand, helps ease the pressure. So does charging during midday, when California sometimes has more solar energy than it knows what to do with.

When EVs charge in this mindful manner, using energy during times of day when it’s cheap for utilities to provide it, data suggests they can effectively push down electricity prices for everyone. Says one recent report from Synapse Energy: “In California, EVs have increased utility revenues more than they have increased utility costs, leading to downward pressure on electric rates for EV-owners and non-EV owners alike.” As the NRDC points out, California has revenue decoupling in place for its utilities, so “any additional revenue in excess of what was anticipated is returned to all utility customers — not just EV drivers — in the form of lower rates.”

Those rosy figures depend upon drivers following this model and charging during off-peak hours, of course. But with time-of-use rates giving them the financial motivation to charge overnight rather than in the early evening, it’s not an outrageous presumption.

And there’s something else that differentiates EVs from other applications that consume lots of electricity: Thanks to their ability to store a large number of kilowatt-hours over a lengthy period of time, electric vehicles can give back. EVs can be a cornerstone of the virtual power plant model because the cars — those equipped with bidirectional charging capabilities, at least — could feed the energy in their batteries back onto the grid to prevent blackouts, for example. In Australia, the Electric Vehicle Council recently crunched the numbers to argue in favor of incentivizing residents to install vehicle-to-grid infrastructure. Their math indicates Australia would reap more than the government invests because these connected EV would cut everyone’s electricity price.

It’s getting more expensive for the individual to own an EV — the federal tax credit for buying one disappears at month’s end, and punitive yearly fees for EV ownership are coming. Yet it seems that driving electric might be doing your neighbors a favor, and not just by clearing the air.